Strengthening Immunity Using the Biotic Family In Early Life

Lifestyle factors such as diet, antibiotics and exposure to the environment can modulate the composition of the gut microbiome. Gut microbiota has a profound effect on the host’s immunity and may produce a transgenerational impact on the health of the progeny.1 This article discusses the gut microbiota dysbiosis and the effect of prebiotics and probiotics on host health through microbiota modulation.

What is Gut microbiota dysbiosis?

Gut Dysbiosis can be defined as the altered composition or activity, or both of gut microbiota. Gut microbiota dysbiosis during early life due to prenatal exposure, use of antibiotics, and mode of delivery may contribute to the development and progression of diseases like necrotizing enterocolitis, obesity, allergy, irritable bowel syndrome, asthma and type 1 diabetes in later part of the life.2 Particular foods and dietary habits also profoundly influence the abundance of the gut microbiota in adults and infants (Table 1).3

Figure 1: Diagrammatic representation of the role of gut microbiota in immune development during early life (Adapted from Wopereis et al., 2014)5

| Diet | Effect on gut microbiota | Health outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Low FODMAP diet3 |

|

|

| Cheese3 |

|

|

| Artificial sweeteners3 |

|

|

| Dietary Polyphenols3(from coffee, tea, berries and vegetables such as olives and asparagus) |

|

|

| Fiber and prebiotics (GOS & FOS)3,4 |

|

|

FODMAP-fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols; FOS-Fructooligosaccharides; GOS-Galacto-oligosaccharides; SCFA-Short-chain fatty acids; TMAO-trimethylamine N-oxide

Addressing gut microbiota in early life is the right choice

The infant's gut is immediately exposed to a plethora of microbes of maternal and environmental origins during the delivery process. The gut microbiota of infants significantly transforms and reaches maturation (as that of adults) in the first two years of life. However, certain conditions such as preterm birth, cesarean section and extensive antibiotic use significantly affect the infant's gut microbiota and may delay its maturation.5 Delayed maturation of gut microbiota has been linked with the development of health issues later in life.6 The adult human gut contains highly individualized microbiota. Once established, they remain relatively stable over time. Interestingly, the microbiota introduced to the neonatal gastrointestinal (GI) tract has a better prospect of getting established compared to establishing the same microbiota in the adult GI tract.5 Therefore, it seems a viable approach to address gut microbiota dysbiosis in infants using probiotics or prebiotics in the early stages of life.4,7,8

Prebiotics and probiotics are not the same

Prebiotics and probiotics are completely different from one another but often confused to be the same or are frequently used interchangeably. Several studies highlight the pros and cons of these two nutrients. Table 2 illustrates the difference between characteristics of prebiotics and probiotics.

Table 2. Difference between prebiotics and probiotics.9-17 (Adapted from Pandey et al., 2015; Dwivedi et al., 2016; Gourbeyre et al., 2011; Monteagudoet al., 2019; Shoaf et al., 2006; Schley et al., 2002; Quin et al., 2018; Maldonado J, 2019; Soto et al., 2014)

| Definition9 | Probiotics | Prebiotics |

|---|---|---|

|

Live microorganisms, which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefitto the host. For example:

|

Non-viable food components that confer health benefit(s) on the host through the modulation of the microbiota, such as lactobacilli and bifidobacterial. For example: Non-digestible oligosaccharides

|

|

| Ideal characteristics9 |

|

|

| Immune modulation |

|

|

| Safety in infants |

|

|

| The resemblance with human milk |

|

|

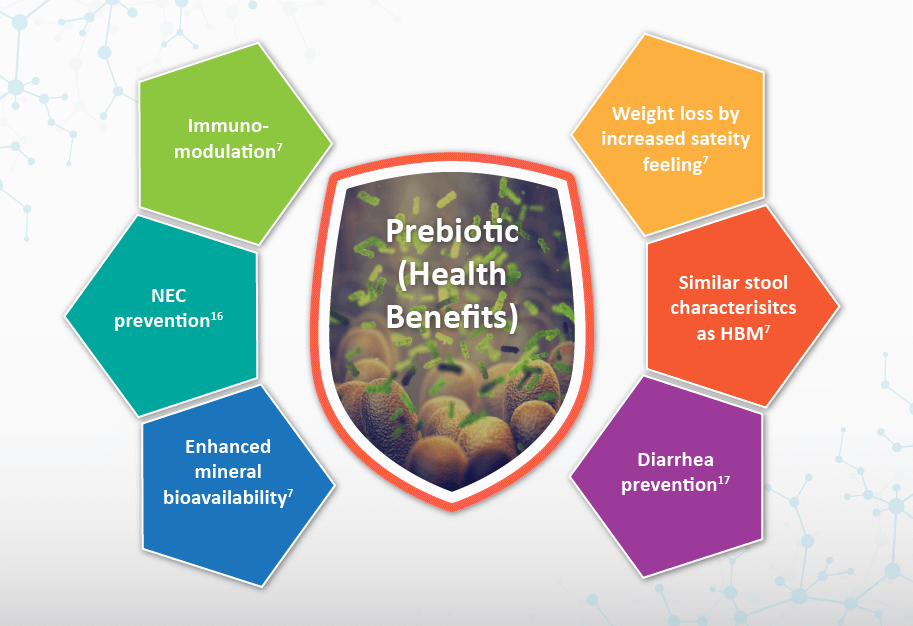

As evident from Table 2 and review of clinical studies, beneficial health effects of probiotics in infants is conflicting.13 Therefore, strengthening immunity using prebiotics in infants would be of significant interest to achieve health benefits (Figure 1). The addition of prebiotics, especially GOS:FOS (9:1)4, and probiotics8 to infant feed, may have health benefits.

Figure 1. Health benefits of prebiotic supplementation at an early stage of life. HBM-Human breast milk; NEC-Necrotizing enterocolitis. (Adapted from Azagra-Boronat et al., 2019; Armanian et al., 2014; Pandey et al., 2015)

Conclusion

In conclusion, complex interplay between prebiotics, gut microbiota and host’s immune system determines the ultimate health outcome. If not addressed, gut microbiota dysbiosis may lead to the development of diseases such as obesity, allergy, irritable bowel syndrome, etc. later in life.2 Dietary fibers have a profound modulatory effect on the gut microbiota.4 Therefore, prebiotics such as GOS and FOS, that resemble human milk oligosaccharides may be useful in restoring the gut microbiota imbalance in infants.4-6

References

- Flandroy L, Poutahidis T, Berg G, Clarke G, Dao MC, Decaestecker E, Furman E, Haahtela T, Massart S, Plovier H, Sanz Y. The impact of human activities and lifestyles on the interlinked microbiota and health of humans and of ecosystems. Science of the total environment. 2018 Jun 15;627:1018-38.

- Amenyogbe N, Brown EM, Finlay B. The intestinal microbiome in early life: health and disease. Frontiers in immunology. 2014 Sep 5;5:427.

- Vandenplas Y, Greef ED, Veereman G. Prebiotics in infant formula. Gut microbes. 2014 Nov 2;5(6):681-7.

- Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, Spector TD. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Bmj. 2018 Jun 13;361:k2179.

- Donovan SH, Gibson GL, Newburg DA. Prebiotics in infant nutrition. Mead Johson & Company. 2009:1-42.

- Zhuang L, Chen H, Zhang S, Zhuang J, Li Q, Feng Z. Intestinal microbiota in early life and its implications on childhood health. Genomics, proteomics & bioinformatics. 2019 Apr 12.

- Conlon MA, Bird AR. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients. 2015 Jan;7(1):17-44.

- Kullen MJ, Bettler J. The delivery of probiotics and prebiotics to infants. Current pharmaceutical design. 2005 Jan 1;11(1):55-74.

- Pandey KR, Naik SR, Vakil BV. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics-a review. Journal of food science and technology. 2015 Dec 1;52(12):7577-87.

- Dwivedi M, Kumar P, Laddha NC, Kemp EH. Induction of regulatory T cells: a role for probiotics and prebiotics to suppress autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2016 Apr 1;15(4):379-92.

- Gourbeyre P, Denery S, Bodinier M. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: impact on the gut immune system and allergic reactions. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2011 May;89(5):685-95.

- Monteagudo-Mera A, Rastall RA, Gibson GR, Charalampopoulos D, Chatzifragkou A. Adhesion mechanisms mediated by probiotics and prebiotics and their potential impact on human health. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2019 Aug 16;103(16):6463-72.

- Shoaf K, Mulvey GL, Armstrong GD, Hutkins RW. Prebiotic galactooligosaccharides reduce adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to tissue culture cells. Infection and immunity. 2006 Dec 1;74(12):6920-8.

- Schley PD, Field CJ. The immune-enhancing effects of dietary fibres and prebiotics. British Journal of Nutrition. 2002 May;87(S2): S221-30.

- Quin C, Estaki M, Vollman DM, Barnett JA, Gill SK, Gibson DL. Probiotic supplementation and associated infant gut microbiome and health: a cautionary retrospective clinical comparison. Scientific reports. 2018 May 29;8(1):8283.

- Maldonado J. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Infant Formulae. InPrebiotics and Probiotics-Potential Benefits in Human Nutrition and Health 2019 Aug 29. IntechOpen.

- Soto A, Martín V, Jiménez E, Mader I, Rodríguez JM, Fernández L. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in human breast milk: influence of antibiotherapy and other host and clinical factors. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014 Jul;59(1):78.

- Armanian AM, Sadeghnia A, Hoseinzadeh M, Mirlohi M, Feizi A, Salehimehr N, Saee N, Nazari J. The effect of neutral oligosaccharides on reducing the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: a randomized clinical trial. International journal of preventive medicine. 2014 Nov;5(11):1387.

- Azagra-Boronat I, Rodríguez-Lagunas MJ, Castell M, Pérez-Cano FJ. prebiotics for gastrointestinal infections and acute diarrhea. InDietary Interventions in Gastrointestinal Diseases 2019 Jan 1 (pp. 179-191). Academic Press.